How Many Gas Power Plants Is America Going To Build?

Putting America's gas power plant buildout in context

In the last few years, there have been many news stories about America’s latest gas power plant building boom. The stories tend to go something like this: Generative AI products like ChatGPT require a lot of computing power and electricity. In response to this growing demand, utilities are planning and building new gas power plants faster than we have in recent memory.

Last week, Reuters published a story that featured gas power predictions and forecasts from consulting groups like McKinsey and Wood Mackenzie. They wrote:

Over 100 GW of new gas-fired projects have been announced, Jay Kim, Associate Partner at McKinsey, said. Not including small projects and those without completion dates, around 120 gas-fired plants are planned by 2030 for a total capacity of around 80 GW.

"To put that number in perspective, over the last five years the U.S. added only about 35 GW of gas," Kim said. "So, it's almost triple what it was."

But left unsaid was the fact that much of this capacity will never be built.

It’s easy to read the quote from McKinsey’s Jay Kim as saying gas capacity additions are about to grow by a factor of three. But that’s not what he’s saying. He’s saying that three times more gas plants have been announced than were actually built over the last five years.

The difference between what is announced and what is built is historically very large and is worth keeping in mind when reading about gas plant announcements.

Most proposed gas plants are never built

There are more than 2 terawatts (TW) worth of power capacity waiting to connect to the US power grid today, according to Cleanview’s project tracker. The vast majority of that capacity is in the form of solar, wind, and batteries. Naturally much of the discourse about the interconnection queue tends to focus on renewables.

Readers of this newsletter have probably heard that most of these projects will never be built. Historically just 14% of proposed solar projects and 11% of proposed battery projects have ever reached final completion.

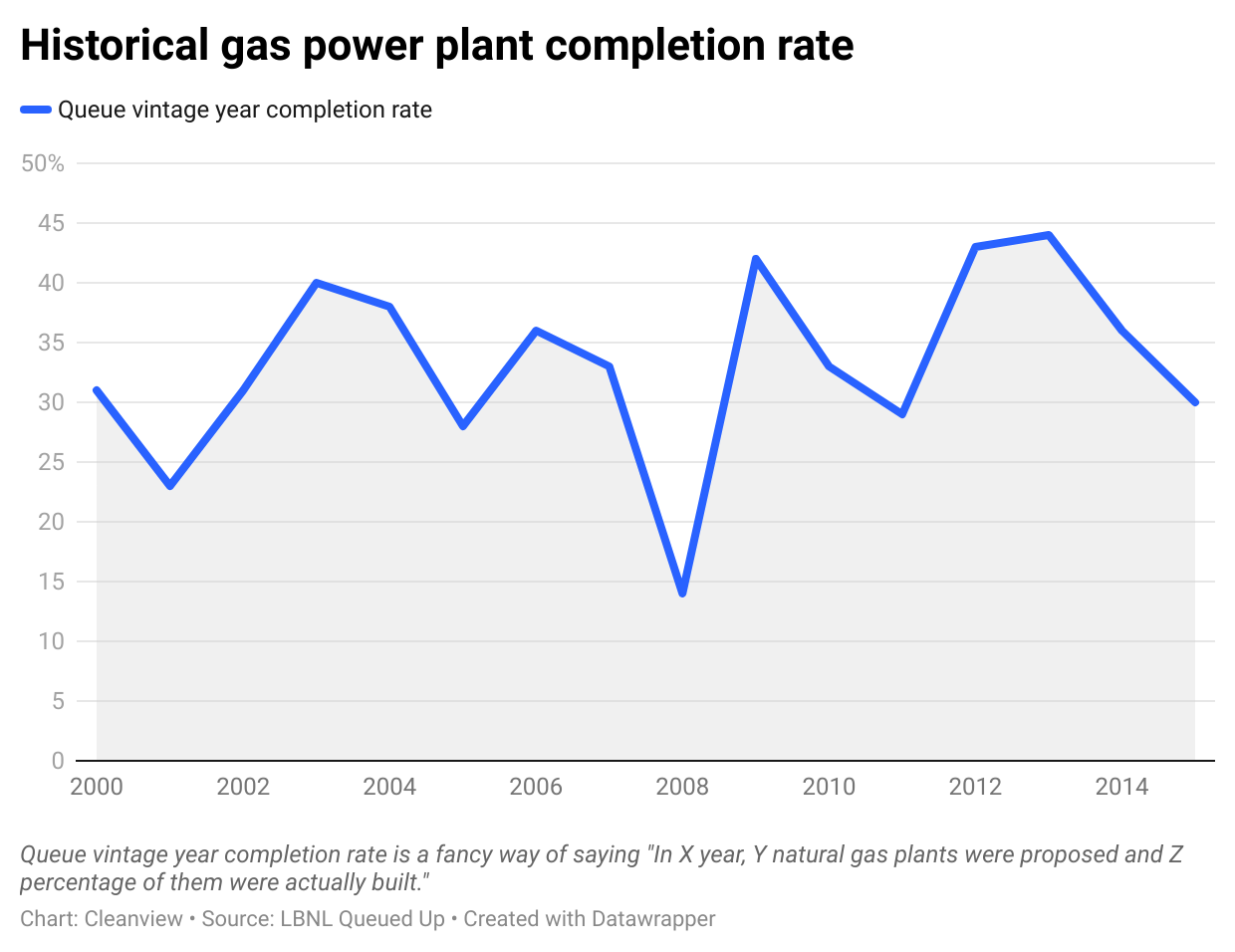

The completion rate for gas power plants isn’t as low as renewables, but it’s still far from 100%. Between 2000 and 2023 just 31% of proposed gas plants reached commercial operation. That means for every three natural gas power plants that were announced over this period, just one was built.

This trend holds true across all regions and energy markets in the US. I would have assumed that the completion rate would be higher in regions where utilities have a monopoly like the Southeast and Western US. But in these regulated markets the historical completion rate is actually even lower than the US average at 28% and 18%.

The future never looks like the past, but it’s safe to assume that many of today’s announced gas power plants will never be built.

The latest gas buildout looks a lot like the past

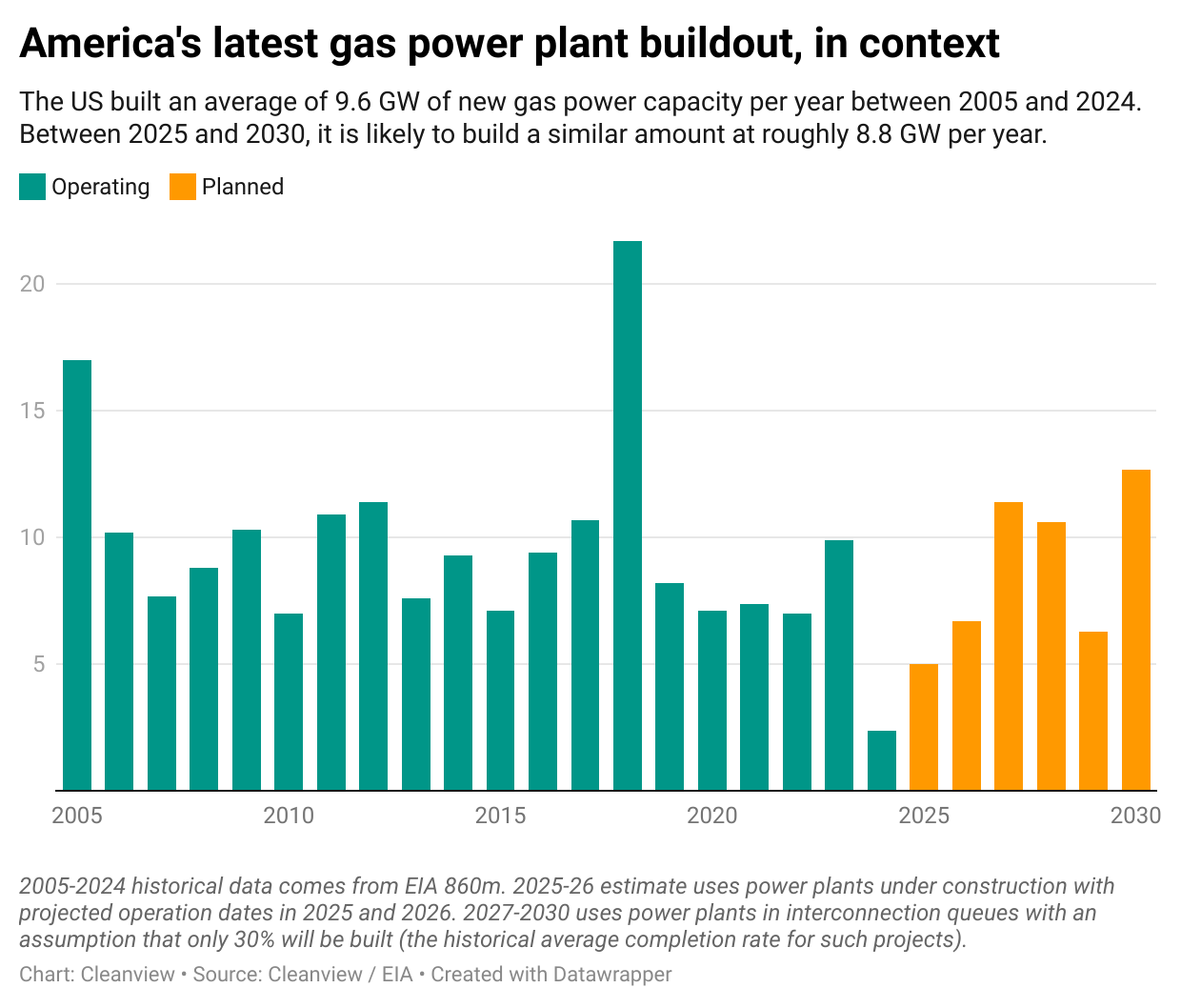

Using data from Cleanview’s project tracker and the historical completion rate data above, I created a back-of-napkin forecast1 to see how much gas capacity could come online by 2030 based on proposed projects. The upshot is that the next 5 years is likely to look much like the last two decades.

Between now and 2030, the US is likely to build 53 GW of new gas capacity, or 8.8 GW per year. That’s much more fossil fuel power capacity than we should be building in a climate crisis. (There are plenty of other ways to meet that demand as I’ve written). But most media stories about this gas buildout describe it as a new phenomenon when its actually a continuation of what’s come before.

Over the last two decades the US built 9.6 GW of new gas power capacity per year on average—a similar amount to what’s likely to come online over the next 5 years.

It would be more accurate to say that 2024 and 2025 with their low gas capacity additions—at 2.4 GW and a projected 5 GW respectively—are the real deviations from the norm.

I haven’t seen any comprehensive analysis of what drove the gas slowdown in these years. But my hypothesis is that it was driven by the wave of utility net-zero pledges that came in the years before and the remarkable growth of renewables and storage—the top competitors to natural gas power.

Where are gas power plants being proposed?

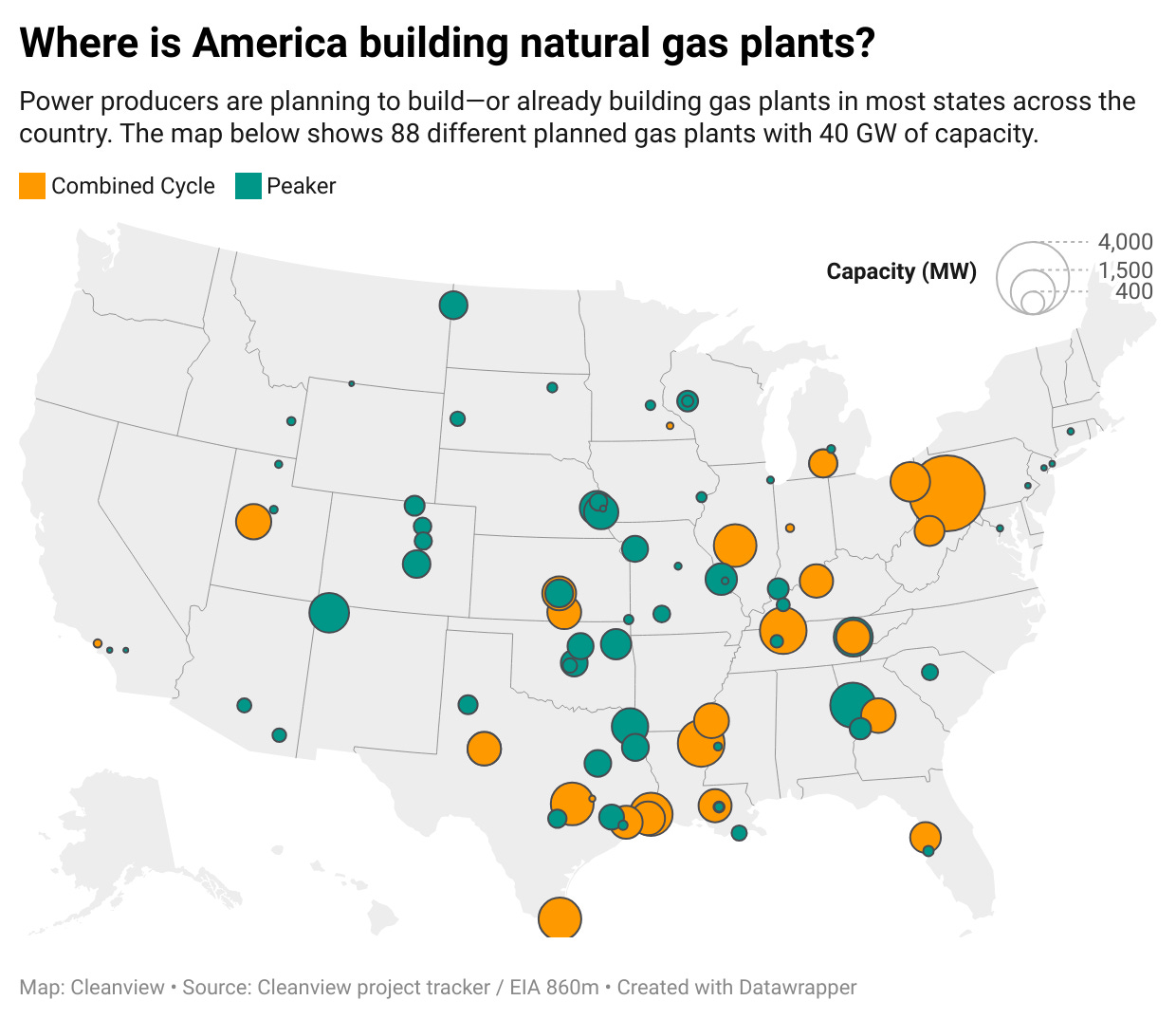

Gas power plants have been proposed in at least 37 states across the country.2 Only a small number of states in the Northeast (where gas pipeline infrastructure is limited) and the Northwest (where hydro plants generate most electricity) are abstaining from building these fossil fuel projects.

The largest proposed project on this map is the massive 4.5 GW gas power plant that is being built at the site of the retired Homer City coal-fired power plant. The project is expected to power a new data center campus.

But not all of the gas plants that have been proposed are the same. 63% of the planned gas projects are combined-cycle plants that are expected to run about two-thirds of the hours in a given year. The remaining 34% are peaker plants that will run a small number of hours each year when demand is highest.

To me the real story of natural gas power is this: For a very short time, America was on track to build far less gas power plants than it had at any time this century. But that time was short lived. Utilities and independent power producers are back to building gas power plants as they have for much of the last half century. The stability of our climate depends on reversing that trend again and forever with cheaper, cleaner alternatives.

Explore planned power projects in the US

Cleanview tracks 10,000+ planned power projects across the US making it easy to do analysis like the one featured in this story and track planned projects. If you’re interested in seeing a demo of the platform, click the button below.

Read more from Cleanview

Emphasis on the back-of-napkin part of that sentence.

Some states like Virginia and North Carolina have proposed plants that I wasn’t able to find latitude and longitude coordinate for. This map shouldn’t be considered as the definitely list of proposed plants. It’s missing at least a few dozen proposed plants.

Two factors not discussed. One is the supply chain, I have been through these gas-generation cycles since the 90's and even then the supply chain was an issue and not just for turbines, but the substation components. Second is will these gas projects be simple cycle, co-generation, or combined heat and power (CHP). Co-gen or CHP are more efficient and the actual emissions per MW generation goes down.

Thank you for this analysis! I'm curious how the reported backlog of natural gas turbines factors into this. Source: https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/electric-power/052025-us-gas-fired-turbine-wait-times-as-much-as-seven-years-costs-up-sharply