Bypassing the Grid: How Data Centers Are Building Their Own Power Plants

An analysis of 46 behind-the-meter data centers and the equipment powering them

Many data centers claim to use clean energy to power their operations. But in a report Cleanview published today, we found that’s increasingly not true. Instead data centers are using natural gas—and doing so in very strange ways.

It can now take as long as 7 years to connect a data center to the power grid. Beginning about a year ago, developers began pursuing new power strategies. Rather than wait, many data centers are now building their own power plants.

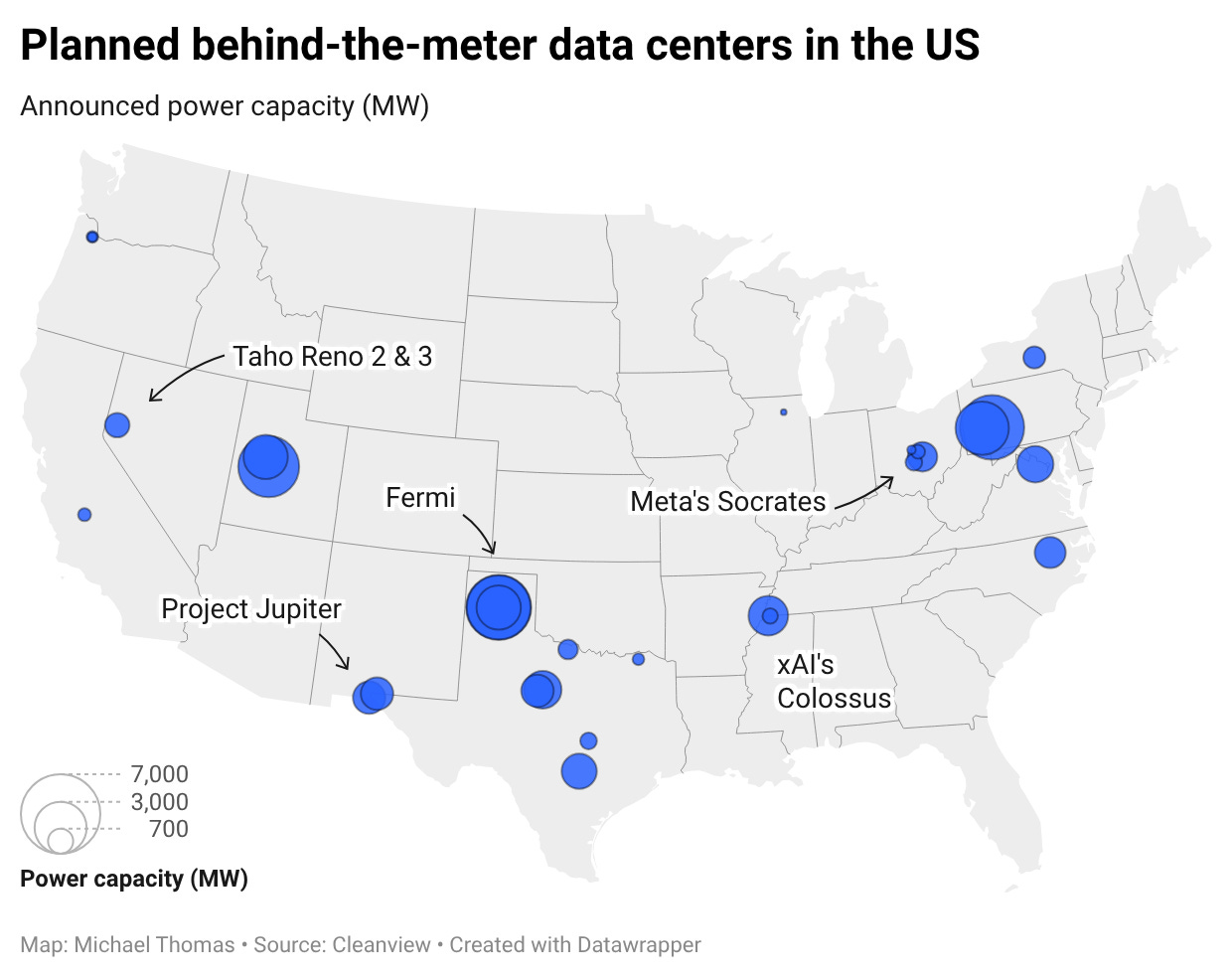

In what we believe is the most comprehensive analysis of this trend to date, we identified 46 data centers with a combined capacity of 56 GW that plan to build their own power “behind-the-meter.” That represents roughly 30% of all planned data center capacity in the United States, according to Cleanview’s project tracker.

In the last year, this trend has gone from niche to mainstream. 90% of the projects we identified—representing approximately 50 GW—were announced in 2025 alone. A year ago, behind-the-meter data center power was a curiosity, embodied by xAI's controversial decision to truck mobile generators into Memphis. Now it's an increasingly common development strategy.

When we began this research, we were skeptical of many of these projects—as all analysts should be. Data center developers often pursue multiple projects with the intention of only building one (the “phantom project” phenomenon). Turbine manufacturers have said lead times for their equipment now stretch as long as 5-7 years. Local opposition to data centers is rising.

But we think much of this capacity is likely to come online soon. Many of the projects we identified are already under construction—in some cases with crews working through the night. Many of those that aren’t under construction have been permitted and have placed equipment orders.

We were able to identify specific equipment deals at approximately two-thirds of the projects we tracked—commitments to manufacturers like GE Vernova, Caterpillar, Siemens, and Doosan that signal serious intent.

What makes our report unique is that we didn’t rely on press releases, which show what developers say they are going to build. Instead we tracked down actual equipment deals and permits showing site plans.

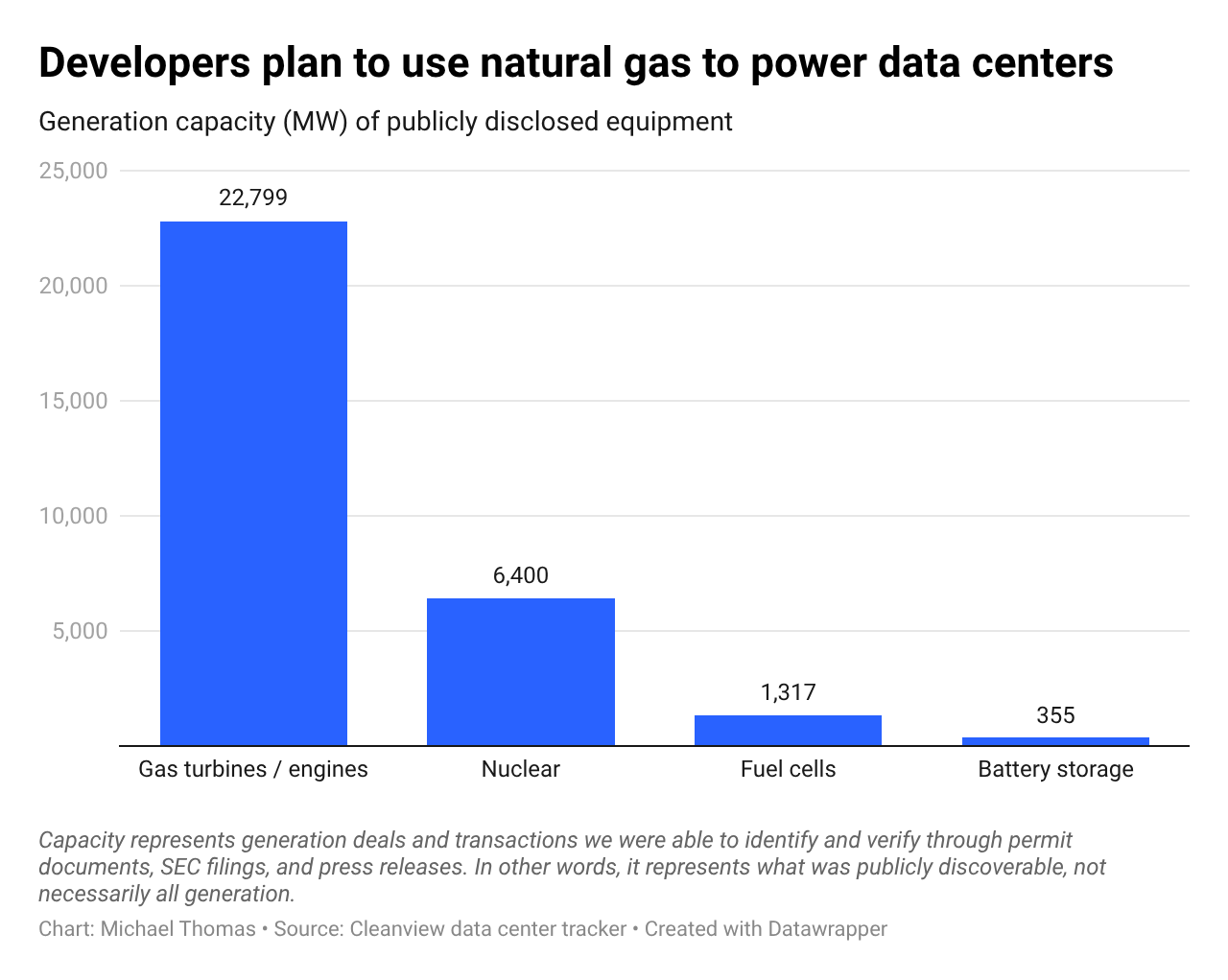

This revealed a very different—and surprising—story. Most of the press releases we found mentioned “all of the above” strategies that include renewables. But ~75% of the generation equipment we could identify (23 GW) was natural gas-powered. Virtually none of the developers planned to build renewables in the short term.

But data centers aren’t planning to use your typical gas turbines—hence why many are able to install them this year or next year. Data center developers are instead turning to:

Mobile gas generators strapped to semitrucks

Aeroderivative turbines originally designed for aircraft and warships

Reciprocating engines that ramp fast, but are less efficient

Refurbished turbines acquired from industrial operations

In our research, we came across a company that typically sells cruise ship engines that struck a deal to power a data center. One developer, unable to secure enough conventional turbines, placed a $1.25 billion order with Boom Supersonic—a company that has never sold a power generation product. Elon Musk's xAI famously drove in semitrucks with natural gas generators on the back to build what was at one time the world's largest data center.

On the surface this makes no sense. These are less efficient technologies and the power will cost far more. But an AI data center can earn as much as $10-12 billion per GW. Getting online a few years early can result in a windfall. Power generation efficiency is out. Speed to power is all that developers care about.

As a company, our main job is to track data centers and power projects. Still, much of this data shocked us. The public narrative is that data centers are waiting for grid connections and 5-7 year turbine backlogs. But that narrative is lagging what is actually happening on the ground in rural counties across the country.

To read the full report, you can head to our website. We’ve released both a free summary and a ~50-page paid version with two datasets. We also have a discounted option for nonprofits and researchers.

The missing element here is natural gas fuel cells. A bunch of companies in that particular supply chain have announced AI datacenter deals. Some of those fuel cells use technologies that could be switched to 'green' hydrogen or 'green' methane (Using solar to power electrolysis of hydrogen from water, then producing methane from captured CO2 + the solar-powered methane). There's also bio-methane, i.e. methane collected from fermenting biowaste like manure from factory farming in digesters to capture methane.

This is a pipeline that's very different, separate, and distinct from the natural gas/methane turbine production line. But yeah, the intent is to build essentially on-site power plants powered by these fuel cells, then eventually transition to the grid, but modulate grid usage against the price of natural gas as arbitrage. Then also if the public demands they not consume grid power, or that they go 'green,' they can swap over to green hydrogen or green natural gas with the same facilities.

AI building these power facilities is actually likely to be the 'fiberoptics' of the AI data center bubble; like the internet bubble built out fiber networks that became profitable after the bubble burst, these data center power plants using the fuel cells creates more of a market for green versions of methane (e-methane, bio-methane) and builds out potential demand for green hydrogen.

Last year WaPo cited the International Energy Agency as predicting that natural gas will provide data centers the majority of their power.

FT, Dec 2025: "Data centre developers are turning to onsite gas generation — where power does not come from the grid — to meet their deadlines. OpenAI’s Stargate facility in Abilene, Texas, is set to include 10 natural gas turbines with a capacity of 361MW. Meanwhile, planning documents outline Meta’s goal to add 200MW of this so-called behind-the-meter generation to its Prometheus cluster in Ohio."